Apache Kafka, Purgatory, and Hierarchical Timing Wheels

Kafka 中有很多HTTP请求需要处理,例如:生产者 ack=all、消费者 min.bytes=1 、集群内部 broker 之间通信,需要跟踪这些请求的状态(成功、失败、超时);

Kafka 会同时有成千上万的异步请求操作同时进行,面对大规模的请求处理,使用 DelayQueue 去跟踪请求状态会有以下问题:

- 请求完成后不能立即删除,需要在后续检查,检查完成的请求,触发删除操作,如果检查删除操作跟不上请求速度,会出现OOM错误;

- 开启一个单独的线程去扫描 DelayQueue,但是频繁的扫描很多 DelayQueue,会有很大的性能损耗(DelayQueue 插入和删除 O(n));

新设计的目标是允许立即删除已完成的请求,并大大减少昂贵的清除过程的负载。 它需要对计时器和请求中的条目进行交叉引用。 另外,由于每个请求/完成都会执行插入/删除操作,因此强烈希望具有 O (1)插入/删除开销。

- Doubly Linked List for Buckets in Timing Wheels (时间轮中桶的双向链表实现,双向链表的优点是,允许O(1)插入/删除一项)

- Driving Clock using DelayQueue (使用 DelayQueue 驱动时间轮,避免时间轮空转消耗资源)

- Purging Watcher Lists (已完成的请求将立即从计时器队列中删除,O(1)开销)

原文地址 Apache Kafka, Purgatory, and Hierarchical Timing Wheels

Apache Kafka has a data structure called the “request purgatory”. The purgatory holds any request that hasn’t yet met its criteria to succeed but also hasn’t yet resulted in an error. The problem is “How can we efficiently keep track of tens of thousands of requests that are being asynchronously satisfied by other activity in the cluster?”

Kafka implements several request types that cannot immediately be answered with a response. Examples:

- A produce request with acks=all cannot be considered complete until all in-sync replicas have acknowledged the write and we can guarantee it will not be lost if the leader fails.

- A fetch request with min.bytes=1 won’t be answered until there is at least one new byte of data for the consumer to consume. This allows a “long poll” so that the consumer need not busy wait checking for new data to arrive.

These requests are considered complete when either (a) the criteria they requested is complete or (b) some timeout occurs.

The number of these asynchronous operations in flight at any time scales with the number of connections, which, for Kafka, is often tens of thousands.

The request purgatory is designed for such a large scale request handling, but the old implementation had a number of deficiencies.

In this blog, I would like to explain the problem with the old implementation and how the new implementation solved it. I will also present benchmark results.

Old Purgatory Design

The request purgatory consists of a timeout timer and a hash map of watcher lists for event driven processing. A request is put into the purgatory when it is not immediately satisfiable because of unmet conditions. A request in the purgatory is completed later when the conditions are met or is forced to be completed (timeout) when it passed beyond the time specified in the timeout parameter of the request. In the old design, it used Java DelayQueue to implement the timer.

When a request is completed, the request is not deleted from the timer or watcher lists immediately. Instead, completed requests are deleted as they were found during condition checking. When the deletion does not keep up, the server may exhaust JVM heap and cause OutOfMemoryError.

To alleviate the situation, a separate thread, called the reaper thread, purges completed requests from the purgatory when the number of requests (either pending or completed) in the purgatory exceeds the configured number. The purge operation scans the timer queue and all watcher lists to find completed requests and deletes them.

By setting this configuration parameter low, the server can virtually avoid the memory problem. However, the server must pay a significant performance penalty if it scans all lists too frequently.

New Purgatory Design

The goal of the new design is to allow immediate deletion of a completed request and reduce the load of expensive purge process significantly. It requires cross referencing of entries in the timer and the requests. Also it is strongly desired to have O(1) insert/delete cost since insert/delete operation happens for each request/completion.

To satisfy these requirements, we designed a new purgatory implementation based on Hierarchical Timing Wheels [1].

Hierarchical Timing Wheel

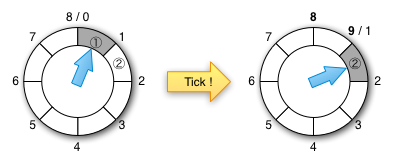

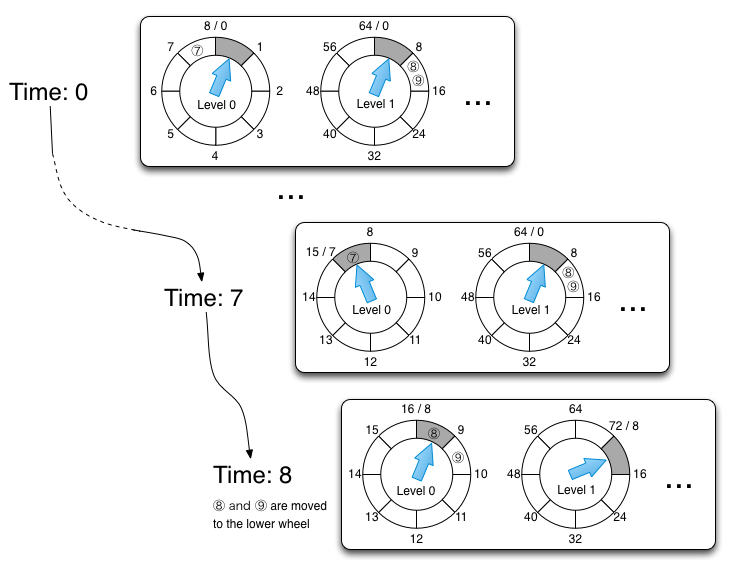

A simple timing wheel is a circular list of buckets of timer tasks. Let u be the time unit. A timing wheel with size n has n buckets and can hold timer tasks in n * u time interval. Each bucket holds timer tasks that fall into the corresponding time range. At the beginning, the first bucket holds tasks for [0, u), the second bucket holds tasks for [u, 2u), …, the n-th bucket for [u * (n -1), u * n). Every interval of time unit u, the timer ticks and moved to the next bucket then expire all timer tasks in it. So, the timer never inserts a task into the bucket for the current time since it is already expired. The timer immediately runs the expired task. The emptied bucket is then available for the next round, so if the current bucket is for the time t, it becomes the bucket for [t + u * n, t + (n + 1) * u) after a tick. A timing wheel has O(1) cost for insert/delete (start-timer/stop-timer) whereas priority queue based timers, such as java.util.concurrent.DelayQueue and java.util.Timer, have O(log n) insert/delete cost. Note that neither DelayQueue or Timer supports random delete.

A major drawback of a simple timing wheel is that it assumes that a timer request is within the time interval of n * u from the current time. If a timer request is out of this interval, it is an overflow. A hierarchical timing wheel deals with such overflows. It is a hierarchically organized timing wheels that delegate overflows to upper level wheels. The lowest level has the finest time resolution. Time resolutions become coarser as we move up the hierarchy. If the resolution of a wheel at one level is u and the size is n, the resolutions should be n * u in the second level, n2 * u in the third level, and so on. At each level overflows are delegated to the wheel in one level higher. When the wheel in the higher level ticks, it reinsert timer tasks to the lower level. An overflow wheel can be created on-demand. When a bucket in an overflow bucket expires, all tasks in it are reinserted into the timer recursively. The tasks are then moved to the finer grain wheels or be executed. The insert (start-timer) cost is O(m) where m is the number of wheels, which is usually very small compared to the number of requests in the system, and the delete (stop-timer) cost is still O(1).

Doubly Linked List for Buckets in Timing Wheels

In the new design, we use own implementation of doubly linked list for the buckets in a timing wheel. The advantage of doubly linked list that it allows O(1) insert/delete of a list item if we have access link cells in a list.

A timer task instance saves a link cell in itself when enqueued to a timer queue. When a task is completed or canceled, the list is updated using the link cell saved in the task itself.

Driving Clock using DelayQueue

A simple implementation may use a thread that wakes up every unit time and does the ticking, which checks if there is any task in the bucket. The unit time of the purgatory is 1ms (u = 1ms). This can be wasteful if requests are sparse at the wheel at the lowest level. This is usually the case because the majority of requests are satisfied before inserted into the wheel at the lowest level. It would be nice if a thread wakes up only when there is a non-empty bucket to expire. The new purgatory does so by using java.util.concurrent.DelayQueue similarly to the old implementation, but we enqueue task buckets instead of individual tasks. This design has a performance advantage. The number of items in DelayQueue is capped by the number of buckets, which is usually much smaller than the number of tasks, thus the number of offer/poll operations to the priority queue inside DelayQueue will be significantly smaller.

Purging Watcher Lists

In the old implementation, the purge operation of watcher lists is triggered by the total size if the watcher lists. The problem is that the watcher lists may exceed the threshold even when there isn’t many requests to purge. When this happens it increases the CPU load a lot. Ideally, the purge operation should be triggered by the number of completed requests the watcher lists.

In the new design, a completed request is removed from the timer queue immediately with O(1) cost. It means that the number of requests in the timer queue is the number of pending requests exactly at any time. So, if we know the total number of distinct requests in the purgatory, which includes the sum of the number of pending request and the numbers completed but still watched requests, we can avoid unnecessary purge operations. It is not trivial to keep track of the exact number of distinct requests in the purgatory because a request may or may not be watched. In the new design, we estimate the total number of requests in the purgatory rather than trying to maintain the exactly number.

The estimated number of requests are maintained as follows.

- The estimated total number of requests, E, is incremented whenever a new request is watched.

- Before starting the purge operation, we reset the estimated total number of requests to the size of timer queue. This is the current number of pending requests. If no requests are added to the purgatory during purge, E is the correct number of requests after purge.

- If some requests are added to the purgatory during purge, E is incremented to E + the number of newly watched requests. This may be an overestimation because it is possible that some of the new requests are completed and remove from the watcher lists during the purge operation. We expect the chance of overestimation and an amount of overestimation are small.

Benchmark

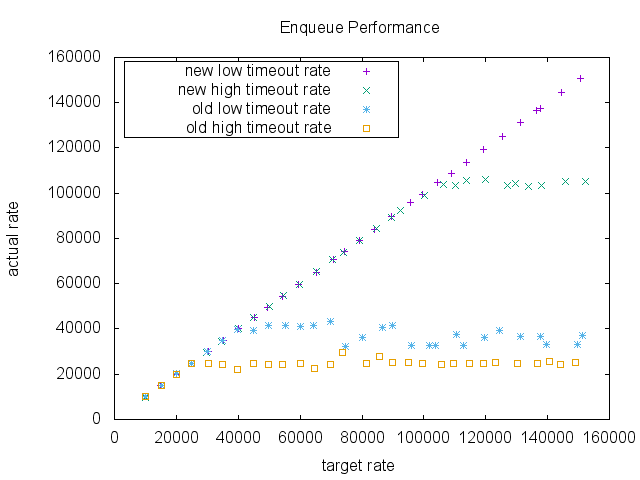

We compared the enqueue performance of two purgatory implementations, the old implementation and the new implementation. This is a micro benchmark. It measures just the purgatory enqueue performance. The purgatory was separated from the rest of the system and also uses a fake request which does nothing useful. So, the throughput of the purgatory in a real system may be lower than the number shown by the test.

In the test, the intervals of the requests are assumed to follow the exponential distribution. Each request takes a time drawn from a log-normal distribution. By adjusting the shape of the log-normal distribution, we can test different timeout rate.

The tick size is 1ms and the wheel size is 20. The timeout was set to 200ms. The data size of a request was 100 bytes. For a low timeout rate case, we chose 75percentile = 60ms and 50percentile = 20. And for a high timeout rate case, we chose 75percentile = 400ms and 50percentile = 200ms. Total 1 million requests are enqueued in each run.

Requests are actively completed by a separate thread. Requests that are supposed to be completed before timeout are enqueued to another DelayQueue. And a separate thread keeps polling and completes them. There is no guarantee of accuracy in terms of actual completion time.

The JVM heap size is set to 200m to reproduce a memory tight situation.

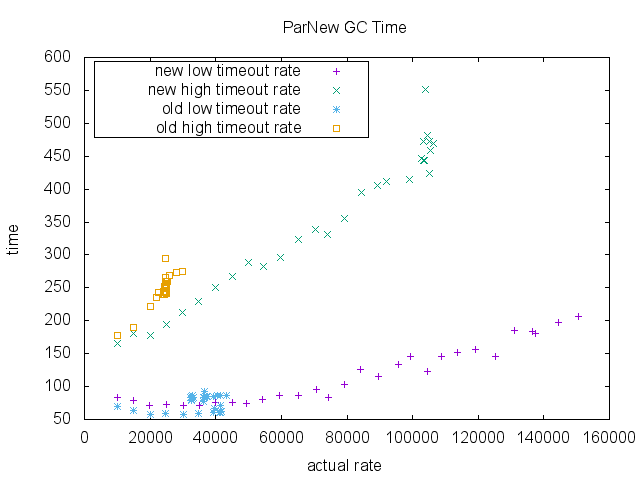

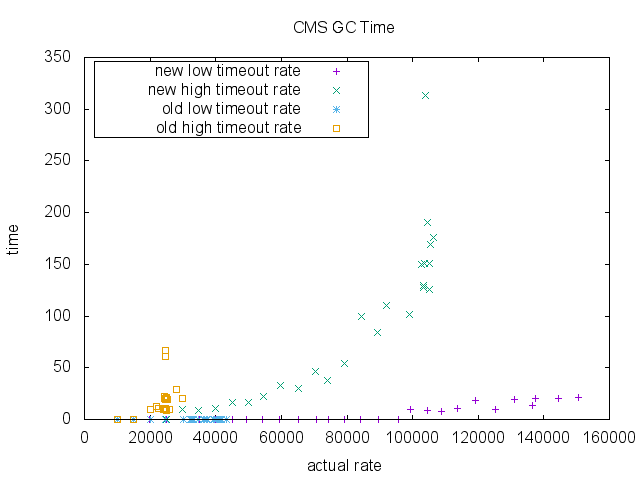

The result shows a dramatic difference in a high enqueue rate area. As the target rate increases, both implementations keep up with the requests initially. However, in low timeout scenario the old implementation was saturated around 40000 RPS (request per second), whereas the new implementation didn’t show any significant performance degradation, and in high timeout scenario the old implementation was saturated around 25000 RPS, whereas the new implementation was saturated 105000 RPS in this benchmark.

Also, CPU usage is significantly better in the new implementation. Note that the old implementation does not have data point higher than ~40000 RPS due to its scalability limit. Also notice that its CPU time saturates around 1.2 while it is steadily going up in the new implementation. It indicate that the old implementation may be hitting a concurrency issue due to synchronizations.

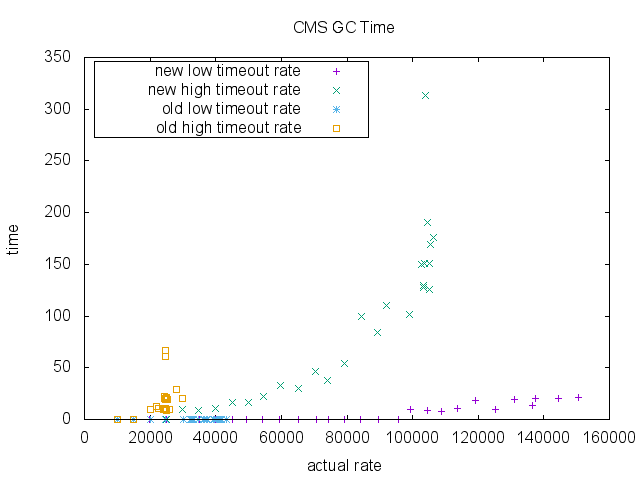

Finally, we measured total GC time (milliseconds) for ParNew collection and CMS collection. There isn’t much difference in the old implementation and the new implementation in the region of enqueue rate that the old implementation can sustain. Again note that old implementation does not have data point higher than ~40000 RPS due to its scalability limit.

Summary

In the new design, we use Hierarchical Timing Wheels for the timeout timer and DelayQueue of timer buckets to advance the clock on demand. Completed requests are removed from the timer queue immediately with O(1) cost. The buckets remain in the delay queue, however, the number of buckets is bounded. And, in a healthy system, most of the requests are satisfied before timeout, and many of the buckets become empty before pulled out of the delay queue. Thus, the timer should rarely have the buckets of the lower interval. The advantage of this design is that the number of requests in the timer queue is the number of pending requests exactly at any time. This allows us to estimate the number of requests need to be purged. We can avoid unnecessary purge operation of the watcher lists. As the result we achieve a higher scalability in terms of request rate with much better CPU usage.